AppleInsider may earn an affiliate commission on purchases made through links on our site.

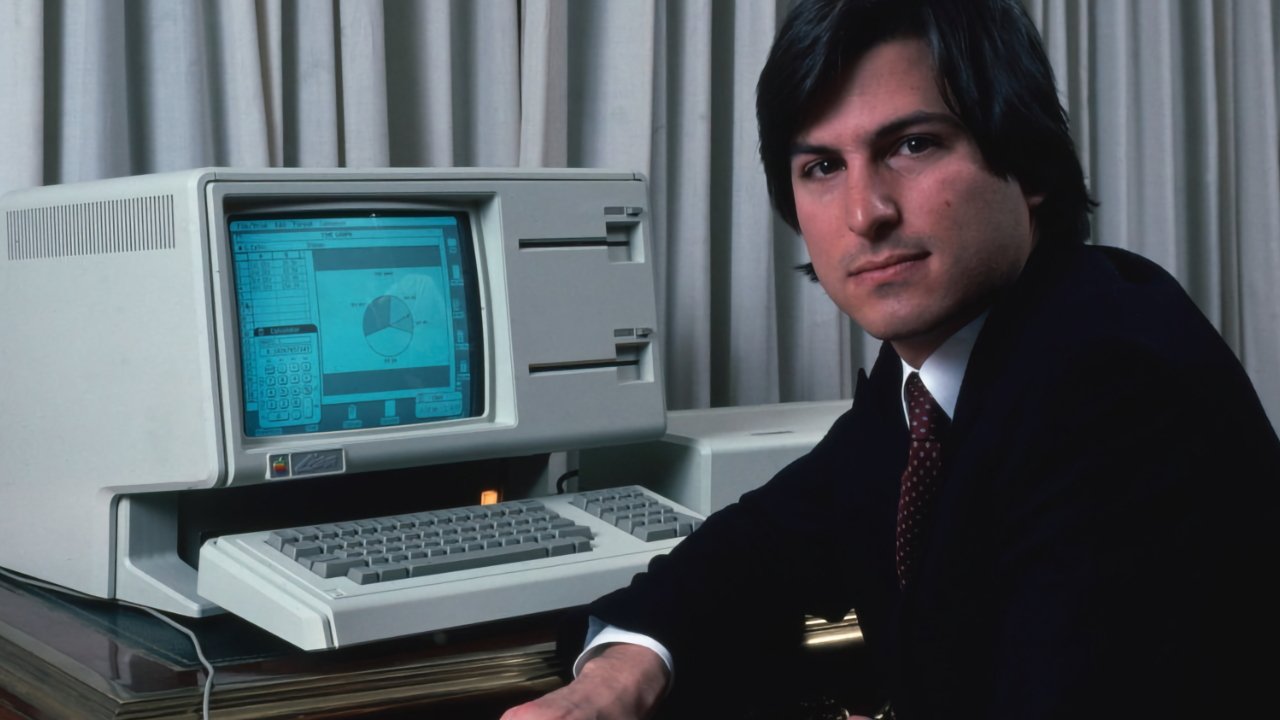

Just about everything the Mac brought to technology was already there a year before with the failed Apple Lisa, that launched on January 19, 1983.

It wasn’t a public launch, it wasn’t anything like the kind of presentation you now expect from Apple. The Apple Lisa was unveiled at the Flint Center, later where the Mac, the iMac, the iPhone 6, and the Apple Watch were later.

That famous venue permanently closed in 2019 — although according to Apple Maps and Google Maps in January 2023, the planned demolition has yet to happen. Part of the De Anza College in Cupertino, its closure was marked with many tributes, practically none of which mentioned the Apple Lisa.

Perhaps that’s chiefly because the Lisa is forgotten, overshadowed by the Mac that followed. But it could also be because that launch 40 years ago was practically a private one.

Apple Lisa’s main launch

That’s from the January 14, 1983 internal Product Introduction Plan, and possibly proves why we needed computers like the Lisa and the Mac, or at least their legible printers.

The marketing plan for 1983 to 1985 was written by David T. Craig and approved by Apple executives. Significantly, those executives did include John Couch, one of the key people behind the Lisa, but it did not include Steve Jobs.

“January 19, 1983, marks the end of a long development effort to bring Lisa to market, but also the beginning of a new era in personal computing,” says the plan. “On that date at the annual shareholder’s meeting, Lisa will be officially announced with simultaneous announcements in other apple [sic] countries throughout the world.”

There’s no record of the simultaneous announcements worldwide, and not much more about the main one at the shareholders meeting.

Today those meetings are often heated and controversial. Back then Apple thought the best place to introduce a business computer was to a business audience.

There was seemingly no filming done and it’s not even possible to be certain who demonstrated the Lisa then. Steve Jobs was involved in some of the promotion, but he’d already been removed from the project and was taking over the Mac.

But you can still get a sense of what was shown, and of how new and different the Lisa seemed in 1983. For there is a video of the Lisa’s first public demonstration at the Boston Computer Society, just one week later on January 26, 1983.

That link starts at the demonstration of the Lisa, but in full the video first shows about half an hour’s launch of the Apple IIe, and then an Apple Lisa promo video featuring Steve Jobs.

It’s a peculiarly ponderous video, whose music soundtrack is just this side of infringing on Ultravox’s “Vienna,” and which barely features Jobs — or anyone.

Although it includes many voice-over comments from Jobs and others, it only shows still images from what were patently videoed interviews.

And the images of Jobs show him with a mustache. He has a mustache, he doesn’t speak on camera, in retrospect it’s as if he were distancing himself from the Lisa.

He’s also careful to lead off with praise not for the computer, but for Apple and its people.

“If you sort of dig beneath the surface,” says Jobs, “one of the real successes of the Lisa program was creating an environment where all these crazy people that could really be very, very successful and I guess that’s one of things that Apple’s done best.”

Apple’s big risk

Jobs had been key in the development of the Lisa, to the extent that it’s named after his daughter. Although he wasn’t acknowledging Lisa Brennan-Jobs at the time, and instead Apple claimed “LISA” stood for “Local Integrated System Architecture.”

We’re not sure we believe Apple’s reasoning behind the name, but Apple had been working on this computer since 1978 so by its launch, it had seemingly had five years to come up with a better name.

Five years is a long time to develop a machine, especially when so much of what it did was taken from the Palo Alto Research Center at Xerox PARC.

It was an enormous investment, though. It was needed because Apple’s huge hit, the Apple II, could not go on forever, and the company already knew it.

“This is by far and away the most ambitious technical undertaking that Apple has ever attempted,” said Jobs in that same promo video. “And it really is the most massive investment of dollars in human resources and really risk since we did the Apple II.”

“With the Apple II we had all of $1,300 to lose,” he continued. “I think what we’ve done is again, really put all our chips back on the table and said we’re willing to bet the company on this.”

Apple certainly put money and effort into every aspect of the Lisa, including its advertising. As well as the ponderous promo, there was one video that will make you glad you don’t work in ’80s corporate America.

And then there was one that was still focused on dynamic business people, but doubled down on how the Lisa was the first computer where “it works the way you do.”

Apple didn’t expect everyone to sit through 10-minute and 15-minute videos, though. It also made a 70-second ad — that featured a very young Kevin Costner.

Apple’s big failure

Apple bet the company on the Apple Lisa — and lost enough to hurt, but not enough to kill the company. It’s hindsight it appears peculiar that Apple could take that hit and still survive, but that survival is really a testament to the strength of the Apple II.

“In fact, 1983, when all these predictions [of bankruptcy] were being made, was a phenomenally successful year for Apple,” said Steve Jobs in a 1985 interview in — of all places — “Playboy” magazine. The original content is not online, and may not have ever been given the date, but an archive of the full interview is available.

“We virtually doubled in size in 1983,” continued Jobs. “We went from $583,000,000 in 1982 to something like $980,000,000 in sales. It was almost all Apple II-related.”

It’s surprising to see Jobs admitting the importance of the Apple II. He would famously refuse to promote it at the Mac launch and according to the 1984 book “Fire in the Valley,” said the Apple II team was “the dull and boring division” of Apple.

He also told the people working on Lisa, to their faces, that they were failures and “C players.”

But what’s perhaps most surprising of all about the Lisa’s failure is that everyone else saw it coming.

“Rumors and leaks about Lisa have been circulating widely,” said the New York Times on the day of the launch. “But the details are only now being announced… At least one such detail — the price — is a potential drawback: Lisa, which will be available this spring, will sell for $10,000, toward the high end of the industry’s expectations.”

The base specification of the Apple Lisa in 1983 would cost the equivalent of almost $30,000 today.

“I think it’s fair to say that everyone working on [the] Lisa program and everyone outside who has seen the product, wants it,” said Jobs in the ponderous video. “Wants at least one.”

Perhaps. Certainly the BBC bought at least one, and used it to — for the time — revolutionize its weather forecasting.

There were other issues, though.

Superior graphics come at a cost

“We believed that Lisa’s 32-bit technology would usher in a second generation of personal computers and establish Apple as a strong competitor in the important business market,” wrote John Sculley, in his “Odyssey” autobiography.

Sculley became Apple CEO after the Lisa launch but before it shipped, and he rather stressed that fact in his book Some of what he did between the announcement and the shipping was nix a lot of what do sound like poor adverts, but it wouldn’t be marketing the Lisa needed most.

“After it started shipping, however, its weaknesses were slowly revealed,” continued Sculley. “It wasn’t as fast as the IBM PC because the superior graphics capability of the Lisa consumed so much of the machine’s higher processing power.”

“But we believed that users would be willing to sacrifice speed for better graphics and ease of use,” he said.

Apple reportedly created a 100-person strong corporate sales team, but they were paid on commission — and they were just not getting enough companies to buy.

“By early September [1983], we discovered that we would likely sell only 6,400 Lisas, rather than the near 11,000 we knew we could build,” wrote Sculley.

“We publicly disclosed that our backlogs were shrinking and our fourth quarter outlook was discouraging,” he continued. “These disclosures… caused Apple stock to drop eight points in a single day.”

Exit Lisa, enter Macintosh

Steve Jobs was reportedly taken off the Lisa project because he was driving everyone spare with his demands that it become like the Xerox PARC demos he’d had. He then took over the seemingly quiet little Macintosh project from its creator Jef Raskin — and made it like the Xerox PARC demos.

There was an enormous amount more to making a fully graphical computer like the Lisa, and then the Mac, though. But gorgeously, every step of that development was documented.

According to the Folklore.org history of the Mac, the development of Lisa took from 1978 to 1982. Chief among the people working on it was Bill Atkinson, and he took Polaroid photos of each significant step in that work.

It’s a historic collection of Lisa details, but it’s also the birth of the Mac.

Gone and almost forgotten

With Lisa dying and the Mac starting to gain urgent importance at Apple, Steve Jobs was reportedly his old brutal self. According to Owen W. Linzmayer’s 2004 book, “Apple Confidential 2.0,” Jobs consolidated the Lisa and Mac teams.

But then said to the Lisa people that, “You guys really f***** up. I’m going to have to lay a lot of you off.”

It’s not as if the Macintosh launched to glory, or at least not to glory and sales, but it did better than the Lisa and of course is the machine that survives to this day, at least in name.

The Mac was also sufficiently more successful that the Lisa was rebranded as the “Macintosh XL,” and reworked to be able to run Mac software.

It didn’t help. The final Lisa to be made came off the production line on May 15, 1985.

For once, you could even argue that it was a bit of a success as all 5,000 unsold Lisas, plus apparently several thousand secondhand ones, were bought by a firm called Sun Remarketing.

Sun Remarketing then resold an unknown number of them, retrofitted to run Mac software with the MacWorks emulator, and later MacWorks XL that incorporated support for the 128KB ROM that was in the Mac Plus. It’s not clear how successful that effort was, but one AppleInsider staffer recalls them selling for less than a Mac Plus in 1988.

That company did various upgrades to the hardware and reportedly the machines were selling quite well. But again, they weren’t selling well enough — at least for Apple.

In order to get a tax write-off, Apple buried the last 2,700 Lisas it had in a landfill in Logan, Utah. The land use cost Apple $1,716 — about $4,500 today — and the burying was done under armed guard.

It was a forlorn end to a machine that while totally eclipsed by the Mac, really was the origin of everything we know in modern computers.

But then perhaps nothing ever ends, for on its 40th anniversary, the entire Lisa codebase — operating system and applications — has been released by the Computer History Museum. Apple has approved its distribution for non-commercial use, and the whole thing takes up a tiny 30mb.